Kenya’s Constitution Making History can be traced to the period 1890-2010. In 1890, the British started settling in Kenya after the Imperial British East Africa (IBEA) Company had navigated the country. In 1920, the British declared Kenya a protectorate and a colony: a colony in the interior parts of Kenya and a protectorate at the 10-miles coastal strip that was under the reign of the sultan of Zanzibar.

Kenya’s Constitution Making History can be traced to the period 1890-2010. In 1890, the British started settling in Kenya after the Imperial British East Africa (IBEA) Company had navigated the country. In 1920, the British declared Kenya a protectorate and a colony: a colony in the interior parts of Kenya and a protectorate at the 10-miles coastal strip that was under the reign of the sultan of Zanzibar.

There are five phases which define Kenya’s search for a Constitutional order that promotes justice, equality and rule of law.

PHASE 1: 1890-1960

This phase was marked by subordination and subjugation of the local people by colonizers leading to an undying need for freedom. Colonial rule was by decree, ordinances and also was marked by dictatorship of the colonial governor, who represented the queen of England. Africans clamored for land and freedom which had been taken away by the colonizers. However, the northern parts of Kenya were neglected. Marginalization of these people therefore started during this period to date.

The birth of the Legislative Council (LEGCO) in 1944 followed great negotiations in which the colonizers decided to have some Africans to represent African interests. This call for representation increased over the period as seen in amendments to the Lyttleton and Lenox Boyd Constitutions of 1954 and 1958 respectively.

PHASE 2: 1960-1962

This phase was marked by emerging constitutional moments. In this phase, three conferences were organized in London to draft Kenya’s new constitution. In these discussions, some of the key problems in phase one resurfaced. For instance, the Mwambao United Front, coming from the then coastal protectorate, was demanding federalism and to some extent a high level of autonomy for their region. The Maa speaking communities were demanding back their fertile grazing land, which has been deprived off them after signing the ‘Lenana Agreements’ of 1904 and 1908. The Somali and communities in the northern region, which had been marginalized demanded full independence as a country on its own. Thus, the way in which the British administered Kenya came back to haunt the three conferences in Lancaster.

Two political parties stood out. The Kenya African Democratic Union (KADU) rooted for a federal state, and was backed by minority groups including the then settlers. The Kenya African National Union (KANU) pushed for a centralized system akin to how colonialists administered Kenya, and also favored a parliamentary system similar to the one in United Kingdom.

In summary, by the time 1962 came, an independence Constitution was drafted largely ignoring the issues of marginalization and freedom of northern people and coastal protectorate; ignored the question of African administrative structures that had existed prior and during colonialism; and also ignored the claims about land. However, the drafters and parties present agreed that right to own property be constitutionalized; agreed on citizenship can be acquired after birth or through other processes; agreed on an independent judiciary; a parliamentary system; and also agreed that the prime minister and governor co-exist together among other things. All these were to change in the next phase.

PHASE 3: 1963-1991

Kenya became independent partially by having self-government under a prime minister, then later full independence but still with the governor as head of state representing the queen. But before one year was over, the first amendment was passed to abolish this latter post, and equip the same powers to the prime minister. The rain started beating Kenya on this material day.

By 1969, ten amendments had been made that increased powers in the presidency. The independence Constitution was totally modified to suit the power hungry elite, who equipped so much power in the presidency.

Other amendments were made like parliamentary language be both in English and Kiswahili, removing and returning security of tenure for constitutional office holders and creating a de jure one party state.

PHASE 4: 1992-2002

This phase was marked by numerous agitations for change. The pressure both locally and internationally saw Kenya introduce multiparty democracy and other electoral reforms. This period also saw the rise of civil societies and political parties pushing for a new Constitution and certain reforms geared towards de-centralizing power around the presidency.

In this phase, three critical steps were taken. First was to forge a common ground for reforms, within the Ufungamano Initiative. Second was to organize and push for legislative framework to govern the process. And third, was the push for further Constitutional amendments under the Inter-Party Parliamentary Group (IPPG).

This period also saw the commencement of writing a new Constitution for Kenya by Kenyans. The Bomas process saw representatives from across the country meet and start writing a new supreme law. Finally, KANU and Moi lost power at the end of 2002.

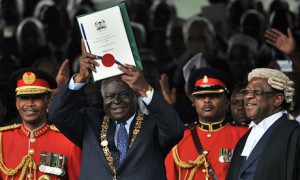

PHASE 5: 2003-2010

In Kenya’s history, this is the most promising phase in the search of a new order. First was the promise by President Kibaki that a new Constitution will be ready within 100 days of taking power but this was not to be. Squabbles about power sharing in the coalition government were evident during the process and the result was the defeat of the proposed constitution in a referendum in 2005. It is argued that this division birthed the post election violence of 2007/8.

After the defeat of the constitutional draft at the referendum, there were efforts aimed at jumpstarting the review. Such efforts included a taskforce set up to investigate why Kenyans rejected that draft; parliamentary attempts by front- and back-bench MPs; and also, political parties’ initiatives to re-start the process. All these were in vain.

Perhaps a reason for the failure to collectively decide on a new constitutional dispensation was the fact that many of those who agitated for reforms now were in power, enjoying the status quo. However, the post-election violence compelled leaders to sit together and map a new supreme law.

A committee of experts was formed to harmonize all documents that informed the reform process primarily: (a) the summary of the views of Kenyans collected and collated by the Commission; (b) the various draft constitutions prepared by the Commission and the Constitutional Conference; (c) the Proposed New Constitution, 2005; (d) documents reflecting political agreement on critical constitutional questions, such as the document commonly known as the Naivasha Accord; (e) analytical and academic studies commissioned or undertaken by the Commission or the Constitutional Conference. This process yielded the current Constitution of Kenya 2010.

Credits to Katiba Sasa Campaign.