No Kenyan has suffered the wrath of Section 29 of the Kenya Information and Communication Act (KICA) like blogger Robert Alai. He has at least five active cases with these charge in court, dating back to 2012. His most recent case this year when the Ethics and Anti-Corruption Commission (EACC) CEO Halakhe Waqo took issue with him for questioning his undergraduate degree in a post on Facebook and Twitter.

The section reads

A person who by means of a licensed telecommunication system—

(a) sends a message or other matter that is grossly offensive or of an indecent, obscene or menacing character; or

(b) sends a message that he knows to be false for the purpose of causing annoyance, inconvenience or needless anxiety to another person

commits an offence and shall be liable on conviction to a fine not exceeding fifty thousand shillings, or to imprisonment for a term not exceeding three months, or to both.

People of all walks of life, especially those in positions of authority took advantage of the ambiguous section to sue others. They would then ensure the case stays in courts for long, with the accused being asked to make frequent trips to courts, only to be told the case will not be heard.

Every week, Jackson Njeru an administrator Buyer Beware Facebook group has been having a court case either in Kwale, Mombasa or Nairobi. Sometimes, he has two cases either in a day, or a day apart in these locations. But he still smiles, abiding by court requirements to appear, however much he knows they are flimsy charges, meant to silence him. He says he is not cowed by any.

The Judgement by Lady Justice Mumbi Ngugi came at an opportune time. It came at a time when Hon. Arthur Papa Odera, the MP for Teso North sued Peter O. Ekisa alias Shujaa Peter for making defamatory statement on Facebook about him. Ruling on 31st March 2016, Justice Mbogholi Msagha fined Peter sh5 million plus costs of the suit. Justice Ngugi alluded to the ruling, citing the use defamation laws as an appropriate piece of legislation.

When you study most of these cases, they merit a charge of defamation. Kenya’s jurisprudence has many cases in which Judges have given stiff penalties for defendants which one wonders why the plaintiffs using Section 29 of KICA do not consider riding on this, especially because they say their reputation is at risk. It only leads to credence that it much more of intimidation and muzzling of freedom of expression than seeking justice.

From penalty perspective, some defamation litigants have been awarded sh30 million and the recent Facebook case sh5 million. However, the maximum charge for Section 29 is three months in prison, sh50, 000 or both. Are these really damages worth loss of reputation?

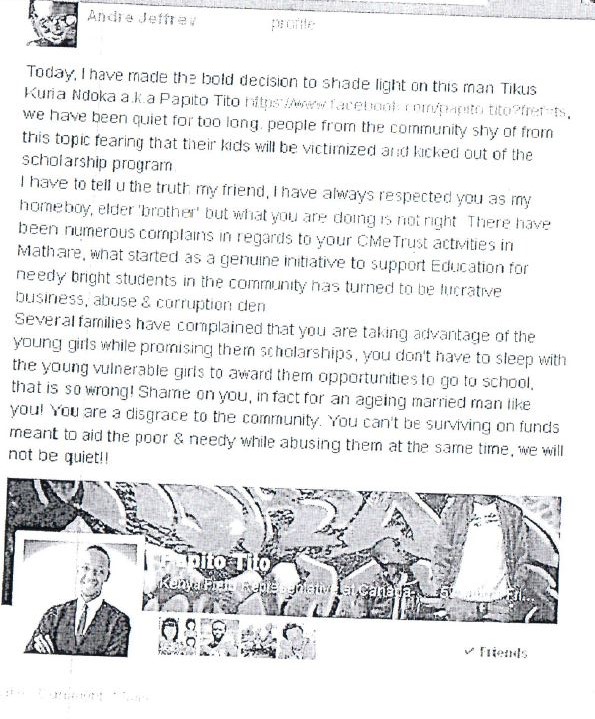

The case came about after Geoffrey Andare was sued by Titus Kuria for what he alleged was posting offensive messages about him on Facebook.

He specifically took issue with these words

“you don’t have to sleep with the young vulnerable girls to award them opportunities to go to school, that is so wrong! Shame on you”

It is after he filed the case that Geoffrey filed a counter suit, challenging the constitutionality of the charge.

Vagueness of wording

The Judge agreed with petitioner (Andare) and interested party (Article 19) in submitting that the words in the section are vague.

The section creates a chilling effect on the guarantee to freedom of expression. It creates an offence without creating the mens rea element (guilty conscious) on the part of the accused person.

She said that failure to define words like ‘grossly offensive’, ‘indecent’ obscene’ or ‘menacing character’ leaves them to the subjective interpretation of the court. She added that determining how a message causes ‘annoyance’, ‘inconvenience’, ‘needless ‘anxiety’ is also very subjective.

She said

It is my view, therefore, that the provisions of section 29 are so vague, broad and uncertain that individuals do not know the parameters within which their communication falls, and the provisions therefore offend against the rule requiring certainty in legislation that creates criminal offences

Limitation of the Right to Freedom of Expression

Both the parties to the case agreed that the section limits freedom of expression. However, the respondents, the Attorney General and the Director of Public Prosecution (DPP) said that the limitation in the section are in line with constitutional limitations in Article 33 of the Constitution

The right to freedom of expression does not extend to-

(a) Propaganda for war;

(b) Incitement to violence;

(c) Hate speech; or

(d) Advocacy of hatred that-(i) Constitutes ethnic incitement, vilification of others or incitement to cause harm; or

(ii) Is based on any ground of discrimination specified or contemplated in Article 27 (4).(3) In the exercise of the right to freedom of expression, every person shall respect the rights and reputation of others.

Justice Mumbi Ngugi however said that the limitation fails to abide by Article 24 of the Constitution which sets general provisions for limitation of rights that they can be limited;

only to the extent that the limitation is reasonable and justifiable in an open and democratic society based on human dignity, equality and freedom.

She added that the limitations do not conform to a free and democratic society as envisioned in the Constitution. She added that respondents failed to demonstrate the relationship between the limitation and its purpose, and to show that there were no less restrictive means to achieve the purpose intended.

Operating license

The learned judge looked into the purpose of the whole law, Kenya Information and Communication Act, Cap 411A

“to facilitate the development of the information and communications sector (including broadcasting, multimedia telecommunications and postal services) and electronic commerce”.

She said that section 24, which deals with the issuance of telecommunication licences did not intend to apply to individual users of social media or mobile telephony.

The Judge added that social media users are not given licenses by the Communications Authority of Kenya (CAK) to operate, warranting meriting of the law.

Individuals such as the petitioner and others who post messages on Facebook and other social media do not have licences to “operate telecommunication systems” or to provide telecommunication “as may be specified in the licence.”

Guilty conscience

The Judge further discussed the issue of the guilty conscience, mens rea, of the petitioner to the crime. This principle in criminal law stated that the court must establish that the accused intended to commit the crime in the mind. She addressed the use of only one sentence by Titus Kuria in suing Andare, forgetting the whole context that the message was sent.

She agreed that failure to establish this guilty conscience means that the right to a fair trial in Article 50(2)(n), a right which cannot be derogated as enshrined in the Constitution was not fulfilled. The section says that you should not be convicted for a crime which is not recognized as a crime in Kenya and a crime under international law.

…as I understand it, is, first, that the absence of the requirement of mens rea offends the central thought that a defendant must be blameworthy in mind before he can be found guilty. I believe that it is not in dispute that crimes involve both blameworthy acts and blameworthy mental elements or state of mind on the part of the accused person.

She ruled that

(a) I declare that section 29 of the Kenya Information and Communication Act is unconstitutional;

(b) I direct each party to bear its own costs of the petition.

The DPP had wanted the case dismissed with costs to the petitioners.

Justice Mumbi Ngugi added that the DPP has the constitutional mandate to determine whether or not to proceed with the prosecution of the petitioner on the case should they disclose an offence under any other provision of law. However ,

the Director of Public Prosecutions cannot continue to prosecute the petitioner under the provisions of section 29 of the Kenya Information and Communications Act.

The judgment, made on 19th April 2016 was welcome news to all Kenyans online.

Excellent site you have here.. It’s difficult to find good quality writing like yours these days.

I really appreciate people like you! Take care!!

Well researched story. The quality of your work is just worth the attention. At least your is not one of those blogs I would describe as gutter. Unfortunately most of our bloggers don’t realize that readers are not fools.If a good reader realizes that you are gutter they will never click a link with your url. Good job!

I love it! Excellent article. You touched on a topical issue. I would appreciate if you’d written about how to fill a form online. Filling out forms is super easy with PDFfiller. Try it on your own here

https://goo.gl/WcayfLand you’ll make sure how it’s simple.